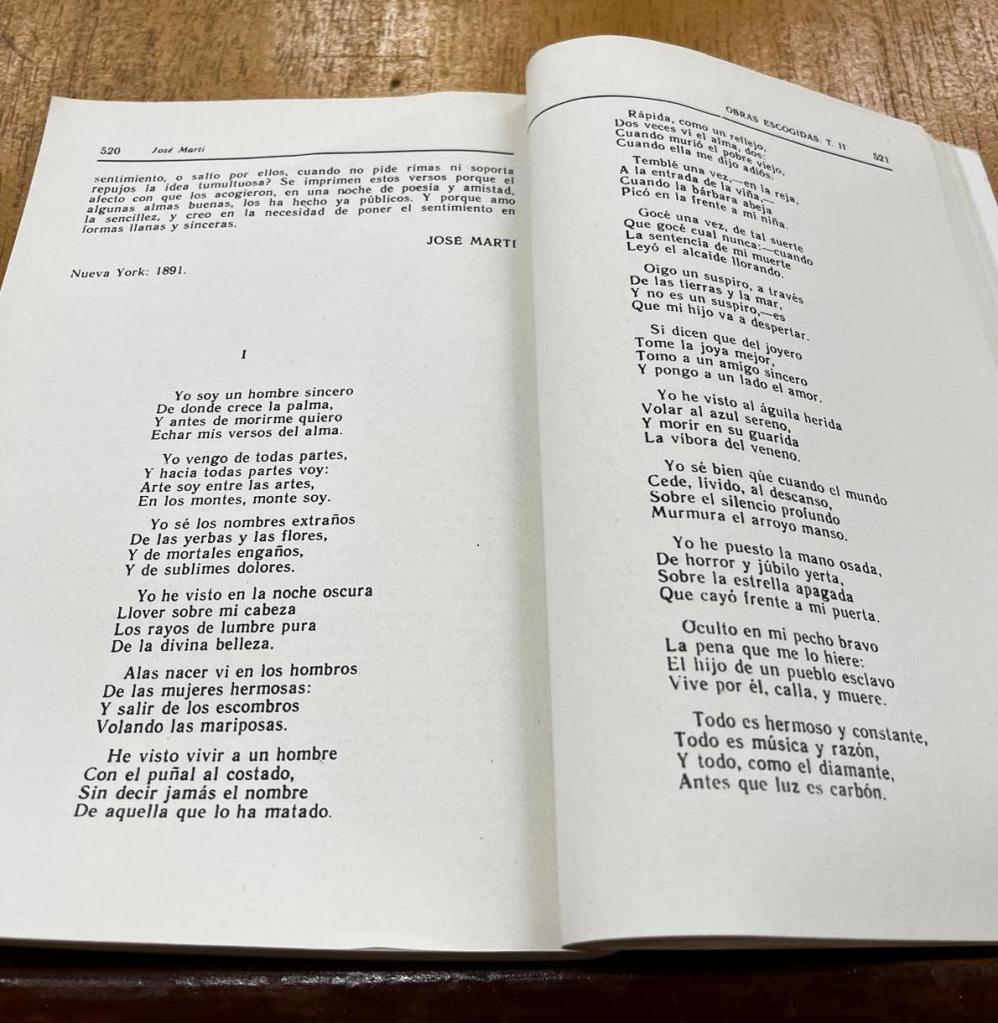

“You have to get to know José Martí,” Gisela told me on my third day in Cuba. Gisela is a kind 50-year-old woman who works at a second-hand book market in Habana Vieja. She showed me — with the patient attitude of a school teacher — the most important pieces of Cuban literature. With confidence and pride, she opened a page of a poetry collection by José Martí and handed it to me. The first stanza of the poem read:

“Yo soy un hombre sincero

De donde crece la palma,

Y antes de morirme quiero

Echar mis versos del alma.”

“In school, we used to learn this poem by heart. I can still remember it word for word,” Gisela added, as she started to utter the verses — her voice filled with emotion. Cuban literature has been a loyal companion throughout her life, and she was delighted to be able to share her knowledge with an interested young person coming from far away.

Education was one of the cornerstones of Cuban society in previous decades, alongside culture, healthcare, and sport. All of these sectors were valued, developed, and made accessible to the whole population as public services — which was one of the main strengths of this once very farsighted Caribbean country. Nowadays, however, the quality and reach of these services are changing, as the economic crisis has brought about disparities in access, a lack of basic goods, a scarcity of personnel — as many young people are leaving the country — and limited renewal and modernisation.

A few days ago, I was walking around the lively Vedado neighbourhood, looking for a library. I came across the Biblioteca Pública (public library), which was right next to the Casa de la Cultura (cultural centre) of Vedado. I entered the old and seemingly empty building. A sign at the entrance announced the imminent start of several music, dance, and folklore courses, which seemed quite intriguing to me. No one was there except for two women chitchatting calmly behind a desk, which I supposed functioned as a sort of reception. I inquired about the possibility of participating in the courses, but they couldn’t give me a definite answer. They called the director of the Casa de la Cultura for me, a well-dressed and gracious woman, who said I might be able to join the courses freely as a foreigner as well. We exchanged phone numbers so that she could let me know (she later confirmed, and I am still waiting for my first lesson on Cuban folkloric traditions). When I asked her whether I could access the library, she said it had been closed that very day due to exceptional circumstances.

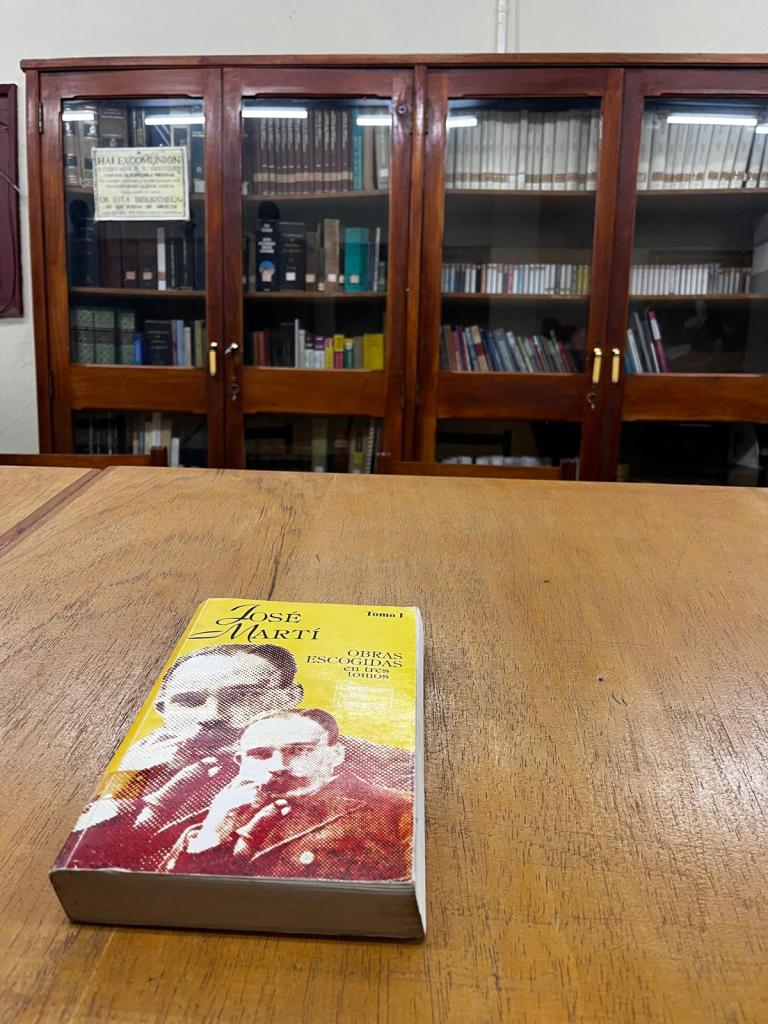

I still wasn’t ready to give up my search for books, so I asked a man on the street whether there was, by any chance, another library nearby. He pointed me to one a few blocks away, which I discovered — to my surprise — was the centre for the study of José Martí’s writings, or Centro de Estudios Martianos. As I walked in, escorted by an employee through a couple of corridors and a large inner patio, it felt like entering an ancient, magical place. It was a beautiful colonial house, painted in an elegant shade of dark pink, with finely decorated white doors and furniture, and a few woody Cuban-style sillones (armchairs) in the patio, flanked by a gorgeous small forest of lush tropical plants.

The library itself was small, filled with ancient tomes, most of them written by or about José Martí. No one was there except for a young librarian named Ana María, who looked at me in a perplexed manner as I entered — I doubt she was expecting anyone that afternoon. After a few seconds of hesitation, she became a little excited about my presence and went to look for a book that would give me some background information about the very house I was visiting. I learned that the house had belonged to the only son of José Martí, Francisco Martí, also known as Pepito or Ismaelillo. After his death, it was turned into a place devoted to the study of the father’s memorable life.

José Martí is one of the most prominent figures in Cuban history. Born in 1853, he was a politician, founder of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, and leader of the Cuban Independence War. In addition, he was a prolific writer, poet, and journalist, leaving many of his thoughts on politics, society, and other matters on paper. I could easily realise the vast extent of his work, as the complete collection of his writings spans more than thirty huge volumes. I opted to dive into his Selected Works for some time, gathered in more than a thousand pages of essays, articles, and poems. I particularly enjoyed his poetry — original and passionate, delving into profound themes through unexpected sources of inspiration (I found a poem dedicated to Chianti wine that was endearing to read). As he defines it in the prologue to his Versos Libres: “These are my verses. They are what they are. I didn’t borrow them from anyone.”

As for the poem Gisela introduced to me (which is part of the poetry collection Versos Sencillos, published in 1891), you might have recognised in its verses the words of the song Guantanamera. Guantanamera is one of the most popular Cuban songs. It was composed by the Cuban musician Joseíto Fernández in the 1920s, even though its melody likely comes from earlier decades, originating in the traditional Cuban styles of son and montuno. The song’s lyrics were adapted by Julián Orbón based on the stanzas of José Martí’s poem. It encloses the words of a man speaking to the “Guantanamera,” a peasant woman from Guantánamo, expressing love and loyalty to his land and friends, as well as solidarity with all the poor people of the world. In the 1960s, the song became an international success, also thanks to the influence of the American folk singer-songwriter Pete Seeger and the vocal group The Sandpipers, who made it part of their repertoire and spread it across the world.

Since then, Guantanamera has become widely known as a hymn of resistance and unity among people, and it has been interpreted by many artists. A version I am particularly fond of is the one by Joan Baez, the “Woodstock’s nightingale,” one of the purest and most beautiful voices the world has ever known (you can find her Guantanamera here). I am happy to mention her, especially now, as Baez turned 85 years old a few days ago and, after a lifetime of commitment, continues to be a voice for justice and human rights through her music, poetry, and social engagement. No one more than her can say “Yo soy una mujer sincera”, using her gifts to fight for what is right — for human dignity, peace, and equity.

When I think about the power of music and poetry and the role they can play in our society, I believe that Guantanamera, José Martí, and Joan Baez provide perfect examples of how we can pour verses out of our souls (“echar mis versos del alma”) to give voice and sound to essential values, commitments, and aspirations for a better — and, importantly, fairer — future.

Leave a comment